Just like humans, dogs and cats have some very important ligaments in their knees. Damage to these ligaments results in pain, instability and lameness.

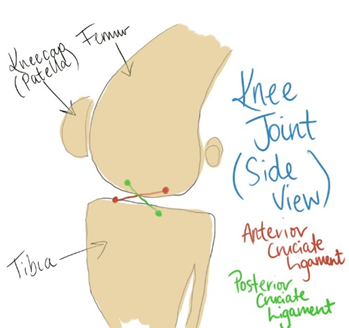

What is commonly referred to as “the cruciate ligament” is actually one of a pair of ligaments in the stifle (or knee) of an animal’s hind leg. It is more correctly known as the cranial (CrCL) or anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). This ligament has the important job of holding the femur and tibia bones together, while still allowing the stifle to bend fully and twist slightly. One of our nurses, Ash, has drawn a diagram below to illustrate the location of the ligaments. The ACL is in red.

ACL injuries are common in humans too. In humans it is typically a traumatic sporting injury – most of us have heard of footballers having a “knee reconstruction”. Cats also occasionally suffer sporting injuries and tear their cruciate ligament.

However, the situation in dogs is quite different. Dogs develop inflammation and degeneration of the ligament which gradually weakens it. Eventually it is so weak it tears completely. The degeneration is not due to trauma or injury, rather a combination of genetics, weight and development.

So, it’s not the football playing that was Rosie’s problem (although that may have been the final straw!)

Cranial cruciate ligament disease is quite common in dogs – 5 % of dogs will develop it. Together with hip dysplasia and patella luxation, it is one of the 3 most common causes of hind limb lameness in dogs. Most breeds can be affected, but we particularly see it in Retriever breeds, Rottweilers, Boxers and Staffies, and many small breeds.

A full ligament rupture causes quite a lot of pain and instability in the leg, and the dog will have a very obvious limp, or may hold the leg off the ground completely. Usually, it is not painful to touch the knee, but it may be painful to bend the knee fully.

A partial rupture or weakened ligament results in a more subtle limp. It may be more obvious after a period of resting or after a vigorous exercise session. It may appear to come and go. Sometimes the signs of a weakened ligament are present for many months before it ruptures completely.

How is it diagnosed?

If your dog has a hind limb lameness, cruciate ligament disease will be on the list of possible diagnoses. Your vet may be able to detect swelling and instability in the joint while examining it during the consult examination. In most cases x-rays are required to confirm the diagnosis and check for other conditions. Sedation or anaesthetic is required for the x-rays, and this allows us to properly check the stability of the ligament while the patient is relaxed. The hips are usually x-rayed at the same time to check that they are healthy, and a sample of joint fluid may be taken to confirm what is causing the swelling in the joint.

What are the treatment options?

Do dogs get knee reconstructions, like the footballers?

Well, yes! Surgery is usually the preferred option to get our patients back to normal athletic ability. The ligament cannot be repaired because it wasn’t healthy in the first place, so the surgery focuses on restoring stability to the knee, and there are several different surgical methods to achieve this.

Here at McDowall Veterinary Practice we perform two different techniques depending on the size of the pet and their athletic potential. The first is called a modified De-Angelis technique, which we use in animals under 12kg in weight. For heavier dogs we recommend the more complicated Tibial Plateau Levelling Osteotomy (TPLO) surgery.

The modified De-Angelis technique replaces the ligament with a synthetic prosthetic ligament. Eventually the body places scar tissue around the prosthesis, which provides long term stability. This has good success in smaller patients, who can more easily cope with putting less weight on the limb as it heals. The recovery period for this technique is about 8 weeks. We find that with this technique there is a more gradual return to full function over the 8 weeks.

The Tibial Plateau Levelling Osteotomy technique is a lot more advanced and requires the precise measurement of the angle of the knee joint which varies from dog to dog. We then remove a section of bone from the Tibia (shin bone), rotate the joint surface of the tibia and fix it in a new position with a metal plate. This enables us to alter the angle of the tibia joint surface so that the instability disappears. This permanently corrects the instability in the joint, so is a much more satisfactory long term solution to the problem as it eliminates the need for the cruciate ligament, rather than replacing it.

We find that this technique is the most successful one for larger dogs, although is increasingly used in smaller patients too. The great thing about TPLO surgery is that the patients are very comfortable within a few days of the surgery and are able to weight bear on that leg more rapidly. This helps maintain muscle mass and results in a more rapid recovery. The TPLO has been shown to have the most successful outcome of all techniques (1,2), which is why we offer this procedure at McDowall Veterinary Practice.

So, when can we get the football out again?

The surgery is just the start of the road to recovery. It will take 8 -12 weeks of strict rest and a gradual re-introduction of exercise before your dog can run off lead again. For a few dogs, full recovery may not be reached until 6 months post-operatively. Following your vet’s instructions during this period is critical in ensuring that the surgery heals well. We will give you an exercise plan to facilitate your dog’s return to function. This will be reassessed and adapted according to each patient as the recovery progresses.

If the healing progresses well, we expect function to return to 95% of the previous exercise ability. Unfortunately, there will always be some arthritis in the joint once cruciate ligament disease occurs. We use pentosan polysulphate injections, omega 3&6 supplements and anti-inflammatory medications to reduce the progression of the arthritis as much as possible.

Can I prevent Cruciate Ligament Disease?

Yes… and no. There are things like breed and genetics that you have no control over. There is some recent evidence that delaying neutering until 12-18m in larger breed dogs may reduce the incidence of cruciate disease (4) as neutering at 6m alters bone growth slightly. However, the biggest difference you can make is to keep you pet slim (3). It is the only cause of cruciate disease that is entirely under our control. Sadly, most pet dogs in Australia are overweight. You should be able to feel your dog’s ribs with only very gently pressure on the skin.

So, to summarise, Cruciate ligament rupture is a common injury, particularly of active middle-aged dogs. It is something that we see a lot of here at McDowall Veterinary Practice and have a lot of experience in. We are fortunate to have state of the art (human) orthopaedic equipment along with two excellent surgeons (Dr Josh and Dr Nicole) who have extensive experience in both of these repair techniques, enabling us to get excellent results. If you think your pet may be suffering from a painful knee, do not hesitate to contact us on 3353 6999 and arrange a discussion with us. We will be able to assess you and your pets individual circumstances and recommend the best course of action for you, ensuring that we have them pain free and back to full function as soon as possible!

References:

- 1. Extended long-term radiographic and functional comparison of tibial plateau leveling osteotomy vs tibial tuberosity advancement for cranial cruciate ligament rupture in the dog. Elisabeth V Moore, Robert Weeren, Matthew Paek. Vet Surg. January 2020;49(1):146-154.

- Long Term Functional Outcome of Tibial Tuberosity Advancement vs. Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy and Extracapsular Repair in a Heterogeneous Population of Dogs. Ursula Krotscheck, Samantha A Nelson, Rory J Todhunter, Marisa Stone, Zhiwu Zhang. Vet Surg. February 2016;45(2):261-8.

- Influence of signalment on developing cranial cruciate rupture in dogs in the UK. P Adams, R Bolus, S Middleton, A P Moores, J Grierson. Small Anim Pract. July 2011;52(7):347-52.

- Assisting Decision-Making on Age of Neutering for 35 Breeds of Dogs: Associated Joint Disorders, Cancers, and Urinary Incontinence. Benjamin L Hart, Lynette A Hart, Abigail P Thigpen, Neil H Willits. Front Vet Sci 7 July 2020; (7) Article 388.